Women’s Journal

Boston, MA 02108 United States

The first issue of The Woman’s Journal, “devoted to the interests of Woman, to her educational, industrial, legal and political Equality, and especially to her right of Suffrage,” featured on its first page an article entitled “Our Presidential Ficitonist.” In it, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, addressed recent remarks by President Ulysses S. Grant:

“Our highly imaginative ruler informs an admiring world that America ‘is blessed…with a population of 40,000,000 of free people.’ Now the plain, unvarnished fact of the matter is that one-half of this ‘population’ is without rights…. What a noble specimen of the lofty-fictitious in writing is this, then, wherein a nation containing 20,000,000 of virtual serfs is described as ‘free people!’”

The Journal released its first issue on January 8th, 1870. It was begun by Lucy Stone and her husband, as well as former Agitator editor Mary A. Livermore, suffragist and poet Julia Ward Howe, and Higginson, who was known largely as an abolitionist. Stone had worked for some years to put herself through Oberlin College, then the only institution of higher education that would admit women. Upon her graduation, she served as an orator for the abolitionist movement, one of the first women to take a public speaking role. In 1855, Stone was married to Henry Browne Blackwell in a ceremony officiated by Higginson. Blackwell promised during their courtship that their partnership would be one of equality, and as a part of their wedding read a protest against marriage laws, which was ultimately published in national papers. Stone was the first recorded woman to keep her last name, lending the epithet “Lucy Stoners” to married women who did not take their husband’s surname.

As Stone was a founding member of both the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) and the Journal, the two became loosely associated, often in opposition to New York’s more radical National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), which was headed by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who disagreed with Stone and other Boston suffragists over their support of the Fifteenth Amendment (granting black men the right to vote). Though progressive for its day, The Woman’s Journal was conservative in comparison to the NWSA’s Revolution, and did not support divorce or the sale of alcohol or tobacco.

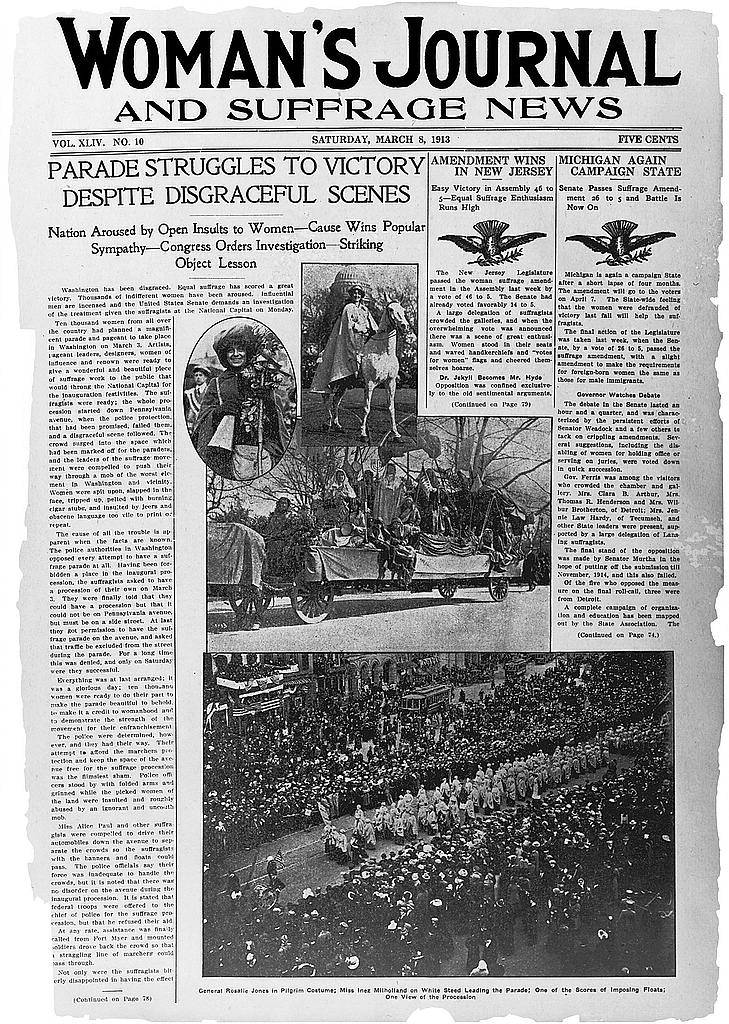

Stone died in 1893, and The Woman’s Journal was briefly helmed by her daughter, Alice Stone Blackwell, who was ultimately able to unite the AWSA and the NWSA as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Women were granted the vote on August 18th, 1920 and The Woman’s Journal ceased publication in 1931.

Upcoming Events

- There were no results found.

Events List Navigation

Events List Navigation

Did You Know?

Certain books were “banned in Boston” at least as far back as 1651, when one William Pynchon wrote a book criticizing Puritanism.