Bronson Alcott’s Temple School

Boston, MA 02111 United States

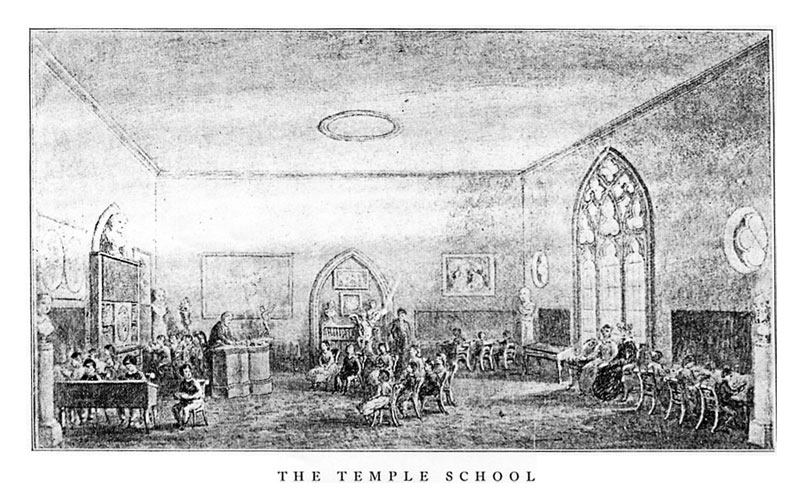

Bronson Alcott’s Temple School, so named for its occupation of rooms in the Tremont Masonic Temple, gained fame and infamy for its alternative methods, operating for less than ten years. Despite its short lifespan, the Temple School employed two of the most prominent female literary figures of the day—Margaret Fuller and Elizabeth Peabody—and contributed to contemporary teaching practices, emphasizing the importance of play and questioning the value of rote memorization.

Alcott founded the Temple School on his abhorrence of corporeal punishment for young children, going so far as to offer his own knuckles for raps, with the belief that all faults are ultimately the teacher’s. This philosophy was eventually expanded outward to encourage personal spiritual development, unmediated by the traditional restrictions of schooling. Alcott believed in four stages of development—marked by the animal nature, the affections, the conscience, and the intellect—which he sought to foster by allowing children to interact with the physical world. He was criticized sharply for his methods, however, and the school dissolved amid scandals when his teaching on the Gospels, circumcision, and even birth control came to light. Elizabeth Peabody chronicled her time at the Temple School in her work A Record of Mr. Alcott’s School.

Though ultimately a member of the Transcendentalist Club and a friend of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau—the latter of whom would borrow Alcott’s ax for the construction of his house on Walden Pond—Alcott’s career struggled. He began working life as a traveling salesman but quickly turned to teaching, which he believed would be better for his spiritual development. Alcott was forced to move his family several times following the closure of his experimental schools; Alcott’s second daughter, Louisa May, would later fictionalize the family’s poverty in Little Women. Despite his skills as an orator, Alcott’s published work in the transcendentalist journal The Dial, an essay entitled “Orphic Sayings,” was deemed so needlessly obscure and nonsensical that it was quickly parodied in the New York magazine The Knickerbocker with a piece called “Gastric Sayings.” Upon the closure of the Temple School, Alcott opened a utopian transcendentalist commune called Fruitlands, based on vegan and agrarian principals, which folded after only seven months. Alcott, who shared a birthday with his daughter Louisa May, died in 1888 and was followed by her two days later.

Upcoming Events

- There were no results found.

Events List Navigation

Events List Navigation

Did You Know?

Certain books were “banned in Boston” at least as far back as 1651, when one William Pynchon wrote a book criticizing Puritanism.