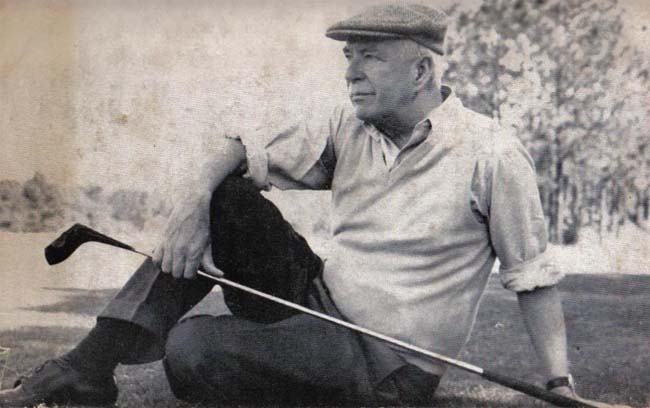

John Phillips Marquand Residence

Boston, MA 02114 United States

“George William Apley was born in the house of his maternal grandfather, William Leeds Hancock, on the steeper part of Mount Vernon Street, on Beacon Hill, on January 25, 1866. He died in his own house, which overlooks the Charles River Basin and the Esplanade, on the water side of Beacon Street, on December 13, 1933… He once said to himself: ‘I am the sort of man I am, because environment prevented my being anything else.’”

So opens the most widely recognized work of John Phillips Marquand, The Late George Apley. The novel, for which Marquand received the Pulitzer Prize in 1938, is a satirical look at Boston’s upper class at the very moment of its decline. Marquand’s mockery was so subtle, and his portrait of Apley “through his own writings” was so compassionate, that the joke was lost upon many readers; Upton Sinclair, writing to Little, Brown in 1936, said, “I started to read it and it appeared to me to be an exact and very detailed picture of a Boston aristocrat… But finally I began to catch what I thought was a twinkle in the author’s eye…”

Marquand was born into a New England family that was itself experiencing financial difficulties. Though he was educated at Harvard, he attended on a scholarship, which made him acutely conscious of class. Following his graduation, Marquand served in the army and worked as a copyeditor. Up until the publication of Apley in 1937, he was known primarily for his serialized spy novels, featuring an aristocratic Japanese secret agent called Mr. Moto. The stories were originally published in the Saturday Evening Post and were later collected into six novels, which were subsequently developed for film and radio.

Marquand showed a marked change with The Late George Apley. He followed the novel with two further satirical works depicting New England’s collapsing upper crust and—after a trio of less successful wartime novels in the 1940s—continued on the theme for the rest of his career. His final book, Women and Thomas Harrow, was widely considered a semi-autobiographical look at Marquand’s failed marriages. With his success, Marquand was able to join the class he had long satirized; he died in his own house, which overlooked land in Newburyport.

Upcoming Events

- There were no results found.

Events List Navigation

Events List Navigation

Did You Know?

Certain books were “banned in Boston” at least as far back as 1651, when one William Pynchon wrote a book criticizing Puritanism.